The 2e Experience

This arts-and-design based research project explores the lives experiences of children identified as 2e or with multiple exceptionalities through the use of a creative probe kit.

About

Brief: For this collaborative research project, we were asked to identify an area of research we would like to pursue using collaborative research methods.

Terms: Twice or Multiple Exceptionality (often called 2e or DME) occurs when an individual has concurrent high ability and learning difficulties (Foley-Nicpon et al. 2013).

Opportunity: 2e/DME neurodiversity is often hidden, misdiagnosed, overlooked, or even unheard-of (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2013). As a result, there is a paucity of research and little understanding of what it means to be 2e. I was identified as 2e as a child and was the only one in my peer group with this identification. For this collaborative project, I wanted to explore whether the sense of community had changed. As a 2e/DME designer and researcher, how can I better understand the 2e/DME experience from more than my own point of view?

Objective: The aim for this collaborative project was to increase understanding about 2e/DME neurodiversity in children through collaborative research methods.

Stakeholders: Educators, Researchers, 2e/DME Children and Parents

Project Development

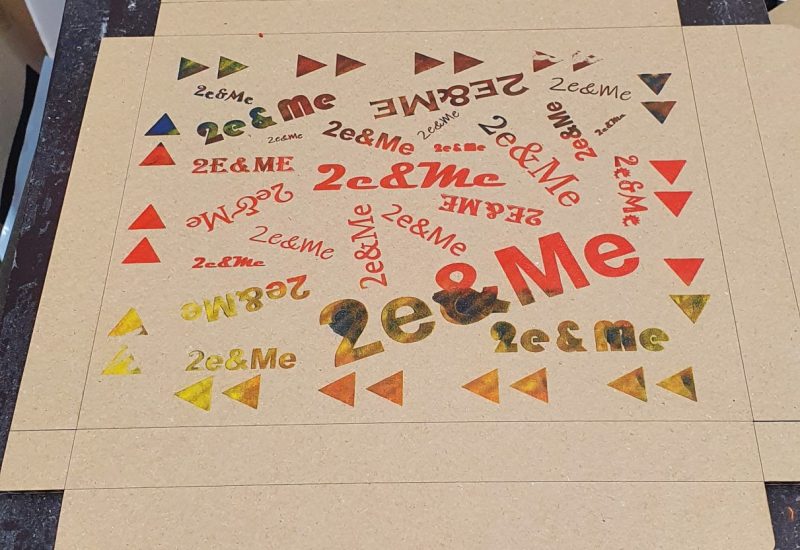

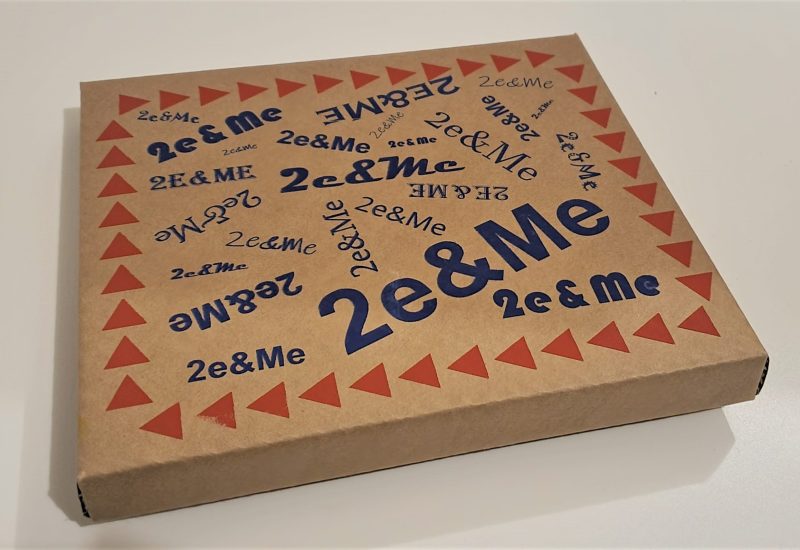

This project was developed to encourage enthusiasm from the participants. Finding participants was the first challenge, which was assisted by a connection made through Mensa. Then was the development of the kit and its contents. While bought boxes were investigated, the final solution included a custom made box – making it more visually and tactically interesting for the participants receiving it through the post.

Journal Entries - Workbook

Below are my design journal entries concerning this project (which make up my digital CRP workbook).

Community Collaboration

The 2e/DME community in the UK is particularly small. Numbers which are available for England show that out of 8.9...

Read MorePackaging & Kit Design

There were many things to consider with the kit creation, including contents, size, cost, and encouraging engagement. Probe Kit Contents...

Read MoreReceiving Responses

The completed kits were sent to the participants homes and they were asked to complete the work within 2 weeks....

Read MoreAdditional Pages

Below are links to additional pages created in relation to this project. The 2e Participant Page includes copies of all the documents sent within the kits.

2e Research Introduction Page

2e Research Exploring the Twice Exceptional Experience Are you the parent of a 2e child? Is your child bright but...

Read More2e Participant Page

Thank you for participating in the 2e & Me Activity. If you have any questions please email heythere@francescadare.com. You can...

Read More2e & Me Hall of Fame

Welcome to the 2e& Me Hall of Fame. Here you will see the fantastic designs and creations of participants in...

Read More2e & Me: The 2e/DME Experience

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lyn Kendall, the participants, and their parents. Without them this project would not have proceeded.

Preface

I was identified with twice-exceptionality as a child and was the only one in my school. It felt strange to be in two worlds at once, as I was put in the gifted education groups as well as support sessions. I opted to stay in my local public school and had an individual education plan put in place as the gifted education programme available in another school did not have experience with 2e/DME children. Also, I had a great group of peers and staying in my own school provided stability. However, being 2e in school was not a straightforward experience, and it is my personal experiences that have inspired this research project.

Keywords

Emancipatory Research, Participatory Design, Twice-exceptional, Cultural Probes,

Introduction

We all have strengths and weaknesses – but the experiences and exceptionality of twice-exceptional (2e) people, those with dual/multiple exceptionality (DME), are distinctive and unique to this type of neurodiversity.

Children with multiple-exceptional neurodiversity exhibit high abilities combined with one or more special educational needs (The Good Schools Guide [no date]). Previously called handicapped-gifted (Yewchuk and Bibby 1989) or gifted learning disabled (Brody and Mills 1997), more recent terms include dual or multiple exceptional (Potential Plus UK 2020) and twice-exceptional (Ronksley-Pavia 2015). 2e/DME children have a double or multiple-neurodiversity identity. In some ways, these children can identify with their gifted classmates, but they can also identify with those who require adjustments for special education needs. They experience a unique diversity that is multifaceted, paradoxical, and often challenging to recognise.

Recent research suggests that approximately 60,000 pupils in England are currently identified as 2e/DME– “a likely underestimate as many are home educated or not identified” (Hawker 2021). Government statistics indicate 8.9 million pupils attend school in England (gov.uk 2021), which means the number of pupils identified with 2e/DME in England is be extremely small, similar to other countries. This small number is likely because 2e/DME is a unique diversity and can be tough to recognise. Students with 2e/DME are often hidden, misdiagnosed, overlooked, or unheard-of (Foley-Nicpon et al. 2013). They are a minority within a minority. In a survey of school psychologists in the US, a majority (60%) had little or no familiarity with twice-exceptionality (Robertson et al. 2011). There also appears to be a lack of UK-based research into understanding and awareness of this unique identity, its strengths, and needs. As a 2e/DME designer and researcher, I wonder how I can better understand the 2e/DME experience from more than my point of view and improve research and awareness.

Aims

As well as satisfying my own curiosity, the ambitions of this research project support the current aims of the Scottish Network for Able Pupils (SNAP).

The current aims on SNAP’s website are:

- “To bring together relevant developments and ideas from a variety of disciplines and initiatives and make them accessible to schools and teachers.” (University of Glasgow [no date])

- “To ensure a strong national awareness of the issues as they arise and support national initiatives that pertain to the education of more able pupils.” (University of Glasgow [no date])

- “To support and model for schools’ appropriate challenges for more able pupils within an inclusive “ (University of Glasgow, n.d.)

While SNAP is concerned with all gifted/highly-able children, this project’s scope only involves those uniquely identified as 2e/DME.

Specifically, this project aims were to:

- Act as a friend to the 2e/DME community

- Encourage creativity, positive thought, and innovation among project participants.

- Better understand the lived experience of 2e/DME children from their perspective and without judgement, prejudice, or stigma.

- Increase awareness of 2e/DME.

Approach

This qualitative research project uses an arts & design-based (Burge et al. 2016) emancipatory research paradigm (Noel 2016) to explore the lived experiences of 2e/DME children. The emancipatory research theoretical perspective in my Design Research and Practice originates in my own experiences of being a 2e/DME creative. The exploration of lived experiences lends itself to a phenomenological approach.

Unlike a positivist research paradigm, which believes in one logical reality that can be scientifically proven, calculated, or observed (Business Research Methodology [no date]), emancipatory research relies on the belief in more than one reality. It is a form of participatory action research that can give voice to both the individual and shared experiences, which is an integral part of this project’s ethos.

“It [emancipatory research] is seen as a process of producing knowledge that can be of benefit to disadvantaged people, and its key aim is to empower its research subjects.”

(Noel 2016, p.457)

My role as a researcher on this project is to empower participants to share their knowledge as experts in their experiences. I act as a research guide, in collaboration with the children as researchers.

Context

The importance of 2e/DME research

One of the barriers to raising awareness about 2e/DME is a general misconception that gifted children do not have learning difficulties. In the early 1900s, research into intelligence focussed on the idea that intelligence is a global construct. Researchers tried to develop intelligence tests to quantitatively measure intelligence in a single score, known as an IQ score, with 100 being average.

In the 1980s, theories of multiple intelligences began to be developed. Howard Gardner’s (1986) theory of multiple intelligences added new ways of thinking about intelligence by changing the definition from a single score to a range of abilities. And Sternberg’s 1988 (cited in Blesch 2012, p.2) triarchic model of intelligence described three attributes of intelligence: analytical, creative, and practical. These theories challenged the idea that someone’s intelligence can be summarized in a single score.

Yet the lack of awareness and understanding about multiple exceptionalities continues (Lucinda 2016). Children who have a multiple exceptionality are hard to spot. Sometimes their ‘giftedness’ hides their learning difficulties and vice versa, making identification difficult. (Lucinda 2016)

The uniqueness of 2e/DME children

The combination of disability and giftedness (high ability) in childhood

For some people, the word ‘disability’ evokes the stereotype of lacking general intelligence (cited in Ronksley-Pavia 2015). This stereotype is inaccurate (Baldwin et al. 2019). Gifted children with vision loss, missing limbs, or other ‘visible’ disabilities are not any less intelligent because of these factors. Similarly, people with learning difficulties can have high intelligence.

The Canadian researcher Françoys Gagné developed a widely-used Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent (Gagné 2008). This model focusses on the developmental nature of high ability, rather than focussing on achievement (Ronksley-Pavia 2015, p.322). Gagné’s model is important as it includes the understanding that children have high cognitive abilities, but they might not be high achievers. This disparity can be particularly true if a 2e/DME child does not receive sufficient support for their learning difficulties, which affects their ability to demonstrate their cognitive potential.

Stigma, Identity, Stereotypes & Bullying

2e/DME children are identified with giftedness and one or more special needs. They are often stereotyped and subject to stigmatization associated with both ‘disability’ and giftedness (Ronksley-Pavia et al. 2019b). Ronksley’s study on 2e/DME children’s lived experiences in Australia reveals that many of these stigmas and misconceptions are prevalent in Western cultures. Both gifted and special needs children have strong feelings of being different from their peers. Despite their identities often being more hidden than other obvious forms of ‘other.’ Due to their strong feelings of isolation and absence of “like-minded peers and traits” (Ronksley-Pavia et al. 2019b, p.8), gifted children are at higher risk of bullying. Children with a disability label often feel feelings of embarrassment and exclusion.

“These children are often teased by their classmates, misunderstood by their teachers, disqualified from gifted programs due to their deficiencies, and unserved by special education because of their strengths”

(Ronksley-Pavia 2015, p.326)

Ronksley-Pavia et al. (2019b) describe the following five main themes in their initial analysis of the children’s interviews: 1. Personal Interests, 2. Negative Experiences, 3. Support Networks, 4. Stress, coping and resilience and 5. Sense of Self. (See Appendix A: Table from “Privileging the Voices of Twice-Exceptional Children”). Their analysis further identified strong similarities between children’s stigma narratives. As someone identified as 2e/DME as a child, I recognised my own feelings and childhood experiences within several of the statements these children said in Ronksley-Pavia et al.’s (2019) interviews, such as:

“I got 98%, so it was an A [grade]. People didn’t believe that I got an A because they think, “He’s got dyslexia how can he get an A?” Everyone’s like, “Well how could he get such a good mark?” . . . . kids thought I cheated.” – Buster (13 years old)

“I was getting dreams about me failing everything . . . One dream, I was just sitting there, and it was the start of the year, and I had just said one word to the teacher, and she said I had failed straight away. . . I normally fail English and I almost failed maths one time, that got me worried, because I don’t like failing. [I feel] sad and annoyed [when I fail]” – Boomstick (aged 10 years)

The children also struggled with their identity due to stigma, stereotypes, and bullying. One child in the study commented that:

“I don’t feel like I’m like this [Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)] . . . I don’t see why I need a label, people have just looked down on me for being labeled as that . . . they think you’re dumber, you don’t have the same ability to do things. I am perfectly able to do the same things as others; sometimes I’m better than what is considered normal. I didn’t want that related to me anymore . . . It was just essentially a label that people could make preconceived judgments about me . . . it was completely useless” – Ashley (16 years)

Identifying 2e/DME children can be challenging for many reasons. Some 2e/DME children try to hide their differences from peers to avoid stigmatisation, bullying, and feelings of being different. Experts agree that identification can lead to several positives, such as greater awareness and improved support for the child, such as appropriate challenges to keep them engaged, as well as greater understanding and compassion from educators (McPherson, 2015; Murawski & Scott, 2017). However, understanding and compassion can be difficult to attain from children’s peer groups who may not fully comprehend the complexities of 2e/DME identities. (Ronksley-Pavia et al. 2019a)

Non-cognitive characteristics

2e/DME children demonstrate contrasts between high ability and low academic performance, but they also exhibit these contrasts in their non-cognitive characteristics (Beckmann and Minnaert 2018). Beckman’s (2018) review of existing literature showed that children with 2e/DME experience elevated levels of frustration. Other potential non-cognitive characteristics include increased perseverance, heightened self-awareness, low confidence, social withdrawal, and negative attitudes toward school (Beckmann and Minnaert 2018, p.16).

2e/DME children often exhibit elevated levels of negative emotions, attitudes, self-perception, and struggle with interpersonal relationships. However, they also show higher than average levels of motivation, resilience, and coping skills, which make up a part of their positive personality traits (Beckmann and Minnaert 2018). In addition to these shared dualities, many 2e/DME children exhibit a remarkably elevated level of “inter/intra-individual variability in their non-cognitive characteristics” (Beckmann & Minnaert, 2018, p.17). Likely, support from parents and teachers and an understanding of their dual identity contribute to this uniqueness within the 2e/DME community.

The importance of children’s involvement in research

While these children vary greatly as individuals, they also have some shared experiences. This research project is interested in the children’s perspective of both areas (individual and collective). Per Articles 12 and 13 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 1989), children have the right to be involved in all activities that affect their lives (cited in Kellett et al. 2004). There are several positives to including children collaboratively in research, but there are also some negatives and limitations. Research with children is often undertaken in a school setting with a captive audience, resulting in a power issue to be considered (Kellett et al. 2004). The practical aspects of skill, competence and knowledge barriers must also be considered. Some researchers have suggested that “children can’t tell truth from fiction; they say what the interviewer wants them to say” (Kellett et al. 2004, p.331). Thankfully, these perspectives have been mostly challenged because it is recognized that “adults are just as likely to blur truth and fiction as children because truth is itself a personal construct.” (Kellett et al. 2004, p.331).

For this research project, I consider the realities of these children’s lives to be truth – as it is their reality regardless of the perceptions of outside adult perspectives (which is why a positivist approach would not have been appropriate in this project).

“There is conflict between the life and experiences of a twice-exceptional child who is first and foremost a child—one who is an active and experienced voice of intellectual strength and maturity—and the disability label he or she receives.”

(Ronksley-Pavia 2015, p.321).

Children can become researchers with appropriate direction, patience, and understanding, even leading their own studies (Kellett et al. 2004). In the context of this project, the children are working as collaborative researchers by creating and collecting data about their lives, thoughts, and feelings. They can express their experiences independently, in the comfort of their own space, without excessively directional or assumptive questioning.

Existing research and design work

As mentioned above, this project follows a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach. This approach has been used with 2e/DME children to collaboratively design and develop strategies for teachers to support the special needs of 2e/DME students. (Haines, 2017). Similarly, Noah from Coloured Fish Products creates t-shirts designs to raise awareness of his dyslexia (Noah, 2014).

An example of a project designed to raise awareness and change stereotypes, Made By Dyslexia opened ‘the world’s first dyslexic sperm bank’ to raise awareness about dyslexia and some famous dyslexics who are considered high intelligence or high achievers such as Albert Einstein. They also collected information about public perceptions and understanding about neurodiversity. Their film about this intervention won the 2018 D&AD Award Pencil (Made by Dyslexia & Y&R London, 2018).

Method

Ethical Considerations

Working with vulnerable groups. As this project involves working with children, I become a member of Disclosure Scotland’s Protecting Vulnerable Groups to complete this project. This scheme helps ensure that people whose behaviour makes them unsuitable to work with children are prevented from doing ‘regulated work’ (mygov.scot 2021).

PVG membership number: 2111 0225 5295 4493

Disclosure Number: 3000 0000 0137 6163

Obtaining parental consent/ children’s assent. The parents/guardians of the participants were given a consent form to review and give permission for their child to participate in this research project. The parents/guardians were reminded that participation is not mandatory, and they or their child can stop at any time (Appendix E).

Maintaining confidentiality. In this report, all participants are anonymized by using pseudonyms and editing identifying information out of photographs.

Participants

This project initially had six people reach out expressing interest to the collaborative partner, Lyn. Three of these participants subsequently contacted me. The three participants included two who were formally identified as 2e/DME and one who self-identified. Out of the three agreed participants, I received two partially completed responses.

A phenomenological approach: Using an arts/design-based cultural probe kit

This phenomenological qualitative research project used an arts/design-based cultural probe kit aimed at engaging children as participants to share their lived experiences.

This style of collaborative research relies on objects rather than talking or watching. This playful approach can help engage communities to express their perspective before we push for change and create opportunities to increase awareness. Engaging the community and the children to be self-reflective through creativity and play enables them to increase their awareness of their identity. The cultural probe kit can be beneficial to gather qualitative data based on participants’ self-documentation, allowing them time and space to complete the task on their own. This style of research is especially useful when working with neurodiverse children who have individual learning, working and expression styles. An arts/design-based approach can be used in both the data collection and data analysis of a research project (Burge et al. 2016)

This project used a probe kit to engage children in an emancipatory paradigm that was explored through the expression of a t-shirt design. This approach encouraged the idea of surprise and “breaking through habitual ways of seeing, thinking and acting” (Burge et al., 2016, p. 731). As the research guide, I encouraged participants to think about the research questions in the hope of exploring “unexpected juxtapositions … leading to insights and deep reflection.” (Burge et al., 2016, p. 731).

This method – using an arts/design-based activity guided through a probe kit – supports an emancipatory approach as it provided the “capacity for immediacy and accessibility and for giving voice to subjugated perspectives.” (Burge et al., 2016, p. 731). Additionally, integrating art into this research project was based on recommendations from Eiserman (2017), who explored arts education and understanding with gifted children in a school setting to address their unique needs. The method supports Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Overexcitabilities (cited in Eiserman et al. 2017), where arts activities allow gifted children to channel their overexcitabilities into “positive avenues of enquiry” (Eiserman et al. 2017, p.208).

Unlike traditional participatory action research, where the entire design of a study is co-created between participants and researchers (Creswell 2018), the cultural probe kit is designed by the primary researcher and includes objects or materials to assist the participant in collecting data about their lives. In this project, the participatory action occurred in the design and making of the t-shirts and the self-creation of data through this arts/design-based method (Sanders and Stappers 2014; Burge et al. 2016; Eiserman et al. 2017; Kassan et al. 2020).

Process

Connecting with the community

At the start of this research project, I contacted two charity partners – Potential Plus UK and the University of Glasgow’s Scottish Network for Able Pupils. Initially, I received a response from Potential Plus UK that my email had been passed onto the Chief Executive. Unfortunately, after unanswered follow-up emails, I could not collaborate with Potential Plus UK for this project.

I also reached out to the Scottish Network for Able Pupils (SNAP) and received positive feedback and interest. Unfortunately, some of my emails landed in their spam folder. Attempts to connect with the SANP contact after their annual leave were unsuccessful.

After some unsuccessful attempts at finding a charity partner, I also attempted to contact the National Association of Gifted Children ([no date]) and the US charity The Davidson Institute for Talent Development (2022) without any success.

Finally, I reached out to British Mensa (2022) using their online contact form and received an encouraging reply. I included the idea of a t-shirt design probe kit in my message to them. They said that the project sounded “very interesting” and connect me with Lyn Kendall, a “psychologist who regularly assesses children and is a former G&T/SEND teacher.” Mensa’s reply was an exciting development in my outreach process. The completed form and full reply can be read in Appendix B: Correspondence with Mensa.

I contacted Lyn, we set up a phone call, and she sent me a copy of her book. Lyn helped this project by giving advice and asked for a poster to share with her parents’ group to find participants. She approved the poster (as shown in Appendix C: Poster for Facebook Group) and shared it with her group, where six people responded. Those who reached out to Lyn were instructed to contact me directly. Out of this first group of six people, two parents reached out to me directly.

I finalized the probe kit and sent photographs and digital files to Lyn for her feedback and review. She gave positive feedback and asked if the additional details could be shared with her parents’ group as they had questions. I agreed with this suggestion as I thought it may encourage more members to get in touch for a kit. (Unfortunately, no further potential participants came forward.)

Developing the probe kit and research questions

I had originally posed the question, “what is it like to be 2e?”. Working closely with Lyn, she suggested there is a risk in asking children such a blunt question, as gifted children often answer questions of that nature with “I don’t know, I am just me.” (Interestingly, she discusses this phenomenon in her book: “A Brilliant IQ: Gift or Challenge?”(Kendall and Allcock 2020)). Lyn suggested a better approach would be to ask more probative and thought-provoking questions, allowing for varied and individualized expression of responses.

While developing the probe kit and design questions, I also sought to create a task that would feel safe to 2e/DME children. Baum et al. (2014) recommend three overarching guidelines for creating programs where 2e/DME students feel safe, including: (1) collecting data in a purposeful way “to gain knowledge of students’ strengths, interests, and talents,” (2) addressing deficits in context “so students can apply and transfer skills in authentic ways” and (3) understanding children’s uniqueness rather than “insistence on measuring them by grade-level expectations.” (Baum et al. 2014, p.323). Baum’s study promotes the use of a “Multiperspectives Process Model” (2014, p.311) (which considers the whole child, both their gifted ability and other exceptionalities simultaneously) with a positive perspective and direct attention to their personal interests and talents. This strategy is a holistic way of assisting 2e/DME students through their learning experiences (Ronksley-Pavia 2015, p.324).

Combining insights from existing literature with the advice from Lyn’s professional experience (and her book) with 2e/DME students, I developed the overall kit concept and research questions. The central concept was to provoke children to reflect on their strengths, their community, and their coping mechanisms. I wantedto ensure the children felt empowered, celebrated, and supported, rather than simply asked what they need help with (which is can easily be the question they are approached with, and they may not be equipped to answer). I also considered how to translate these complex concepts into an activity suitable for a broad age group of 6 to 16 year-olds.

Inspired by Coloured Fish Product’s awareness t-shirts, as well as Dyslexia Scotland’s “Dyslexia is my Superpower” campaign, I asked the children to decorate a t-shirt with their “superpower” on the front, their “superteam” on the back, and their “defence system” on the armband.

The final probe kit included (see also; Appendix D: Kit Photographs):

- Instruction Sheet

- Consent Form

- Activity Guide

- Designer Statement Cards

- White T-Shirt

- White Armband

- Fabric Markers

- Neon Fabric Paint

- Glow Pen

- Metallic Markers

- Transfer Paper

- Crystal Stickers (2E)

The crystal stickers and transfer paper allowed the children to use some collage, so they did not need to feel ‘artistic’ to complete the project. Additionally, the selection of arts and crafts materials were intended to give children choices in how they expressed themselves. For some time, I considered the addition of a tie-dye kit to offer creative alternatives away from the basic white of the t-shirt. However, the size constraints of the bottles I decided not to include this option.

To dig deeper into the participants’ design processes, I included Designer Statement Cards in the probe kit. These cards gave the children the opportunity to explain their designs as an artist might using words, sentences, or even imagery (as thought bubbles were provided.) Minimal instructions were given where possible to allow the children the space to explain their design ideas in the way they felt best suited to.

The children were reminded there were no right or wrong answers and they were not required to use all the kits contents. Specifically, they were asked to “Use the supplies you like in this kit to design your personalized t-shirt & armband following the Activity Guide.” (See Appendix E: Kit Instructions). The activity guide provided design direction and questions for the children to reflect on, as shown in Appendix F: Activity Guide and Designer Statement Cards. It was important to ensure the children knew they had a choice in the creative process, as “choice making can increase student motivation and independence.” (Murawski and Scott 2017, p.23) particularly when working with exceptional learners.

They were encouraged to return their kits by being told they would be displayed on the ‘2e Hall of Fame’.

Developing the kit visuals for children’s enjoyment

The children needed to be engaged with the kit and that there was no perceived stigma surrounding the activity or participating in the activity.

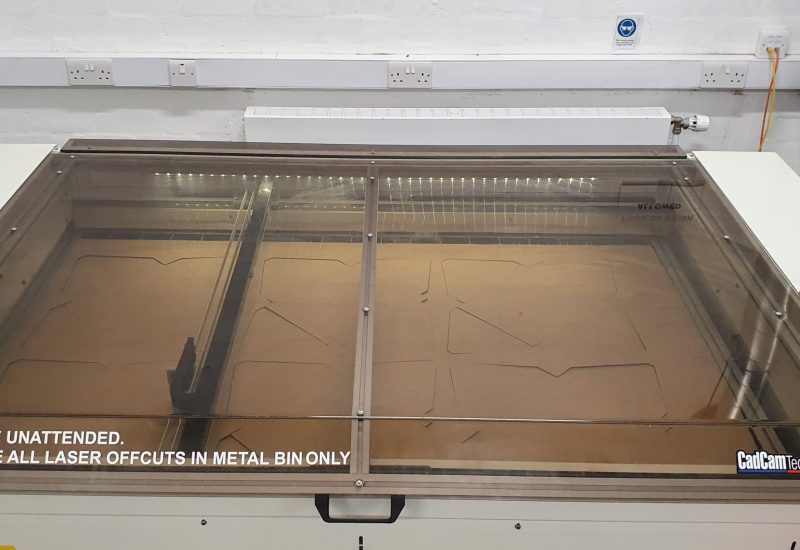

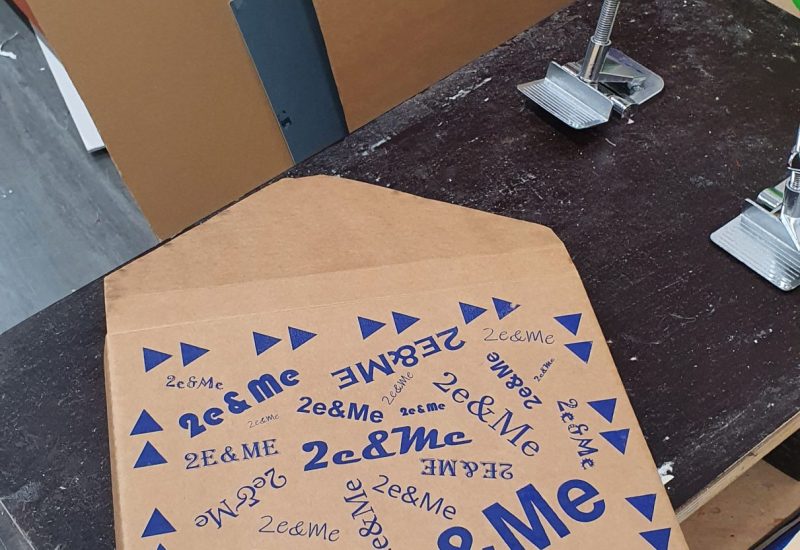

I explored the practical options of sending the kit via Royal Mail as either a Small Parcel or a Large Letter. The Large Letter option was more economical and allowed for the kits to fit through a letterbox, but they are significantly thinner and smaller than a ‘Small Parcel,’ so this was a concern. I purchased a standard white box to send the kit in as a practical option and created two different box designs using the laser cutter. The laser-cut design of a ‘large letter’ appeared the most likely to be exciting to children. It was also compact and kept the kit contents secure.

I worked through graphics options for the exterior of the box as I wanted children to be excited to receive the parcels. The graphic design elements of triangles and vibrant colours used in the poster and kit cards were carried onto the box to resemble a traditional style letter envelope. The final design included the 2e & Me project title over the front of the box in various fonts to represent the uniqueness of the children in the 2e/DME community. (Images 1 & 2)

More photographs and information on the design process of the kit is available here: https://www.francescadare.com/packaging-kit-design/

Online supplemental information

I created a research introduction page and linked it to the initial poster, allowing parents to learn more about the project before coming forward. I also create a participant page to give parents access to digital copies of everything that was in the kit and a link to the 2e Hall of Fame. Copies of these pages can be seen at: https://www.francescadare.com/research/crp/#additionalpages

Further details and information on this project and the process can be found at: https://www.francescadare.com/research/crp/#work

Results and Interpretation

Of the three kits sent out to participants, two returned kits were partially completed, and one kit was not returned. Participant 1 submission can be seen in Appendix G: Participant 1 Response Photographs and Participant 2 in Appendix I: Participant 2 Response Photographs.

Participant 1: Sparrow

Sparrow (not their real name) was a 10-year-old formally identified as gifted with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) and ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder). They were the first to complete a portion of the kit and send in. Their parent emailed in to say that “He [Sparrow] made a mistake at the back and he got really upset and refused to carry on” (Appendix H). It can be common for 2e/DME children to struggle with perfectionism, performance anxiety (Stornelli et al. 2009; Guignard et al. 2012; Baum et al. 2014; Baldwin et al. 2019) and “overexcitability” (Eiserman et al. 2017, p.200). It is understood that “individuals with overexcitability perceive the world not only in different, but also in more intense and multifaceted ways than others; they are much more prone than others to experience surprise and puzzlement at events in their daily lives.” (Eiserman et al. 2017, p.200).

Even when 2e/DME children are interested in the task, or capable of completing it, they can sometimes become too overwhelmed to continue. Sparrow could also be suffering from “internalizing negative experiences” (Ronksley-Pavia et al. 2019b) resulting in anxiety and the inability to participate in activities they enjoy (Ronksley-Pavia et al. 2019b). Children with 2e/DME also “sometimes appear immature by using anger, crying, and withdrawal to express feelings and to deal with difficulties” (Baldwin et al. 2019, p.220), which could be the case here given Sparrow’s age and identification.

Sparrow’s parent reported that “Sparrow really enjoyed creating his design, he planned it and loved the art materials.” (Appendix H). There is some grey literature that children with autism take comfort in organising their things (Comeau 2016), but there is little supporting academic evidence for this. Planning could be a learned technique that Sparrow enjoys and associates with positive outcomes and could be a way of minimising uncertainty in the task ahead, or to try and minimise ‘mistakes’.

Some literature suggests that people with ASD are poor planners (Olde Dubbelink and Geurts 2017), but according to Baldwin et al. 2e/DME children are “often unwilling to take risks with regard to academics or areas of deficit” (Baldwin et al. 2019, p.220), so this could be a demonstration of being risk averse, or one of his “independently developed compensatory skills” (Baldwin et al. 2019, p.220).

As seen in Appendix G, Sparrow completed the front of the 2-shirt, and the corresponding designer statement card (Appendix G, Image 1 & 2).

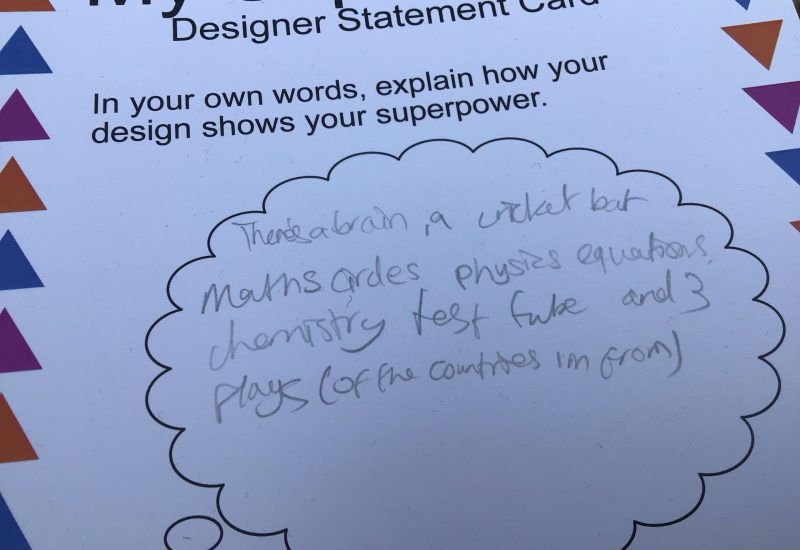

The Designer Statement Card submitted reads: “There’s a brain, a cricket bat, maths, circles, physics equations, chemistry test tube and 3 flags of the countries Im from”.

As 2e/DME is a neurodiversity, it is interesting to see a brain depicted (with 2E placed on top) in Sparrow’s design. It seems fitting to say that his unique brain and way of being in the world is a superpower, as superpowers are depicted in comics as something that differentiates the character. The large multi-coloured cross-style shape could be drawing on classic superhero costume imagery in popular culture. Just like superman has a large S in the centre of his chest, the brain is in the centre of the chest and the cross-style shape, which is likely an indication of the importance that Sparrow places on this aspect. Sparrow also includes imagery that expresses his own cultural background (which makes him unique) as well as academic interests and possible strengths. The design is well planned and shows good visual symmetry – likely as a result of Sparrow’s pre-planning.

A week later, Sparrow completed the armband and corresponding designer statement card (Appendix G, Image 3). It was encouraging to see that Sparrow returned to the activity, but not surprising that he did not re-approach the back of the t-shirt, which is where he had already ‘made a mistake’. Gifted children’s criteria for success is typically higher than their peers (Stornelli et al. 2009) which could be the case here as Sparrow was formally identified as 2e/DME (Gifted with ASD and ADHD). His participation provided valuable insights into his lived experiences. If this activity was performed in-person as part of a workshop, then a better understanding would have been possible, and Sparrow may have been able to complete the project with peer support. His Designer Statement Card reads: “The book is an encyclobedia next to this is a computer these things help me to calm down.” (Appendix G, Image 3).

You can see that encyclopaedia is incorrectly spelt but given his age and the difficulty of the word, this might not be connected to his exceptionalities. English and writing did not make it on the front of the shirt, alongside maths and science. Perhaps Sparrow struggles in these areas, and he may use computers as supportive tools. It is interesting to see an encyclopaedia mentioned as they are not as popular as they once were, but it understandable that Sparrow may enjoy the tactile nature of the books (Sfrisi et al., 2017).

Participant 2: Starling

Starling (not their real name) was an 8-year-old and self-identified as gifted with ASD, ADHD, and OCD. Their submission included only the ‘My Defence’ portion of the kit – the parent had indicated in earlier emails that they had been quite busy. Given Starling’s age and exceptionalities, it could have been difficult to keep their attention regardless of the activity. This could be the case given the ‘My Defence’ portion was the smallest area to design.

Sparrow’s ‘My Defence’ Designer Statement Card reads: “I drew a book cricket, staying away from people, play with my baby sister, go on ipads, draw stuff and running around.” (Appendix I, Image 3). The images of the armband (Appendix I, Image 1 & 2) are slightly difficult to see but there is evidence of multiple colours and shapes.

Compared to Sparrow’s response, Starling’s defence items are more varied and include social regulation. It is possible given Sparrow’s younger age and lack of formal identification that their coping mechanisms are more experimental. They will not likely be receiving supplemental support in school, and so will be relying on compensating techniques. Often 2e/DME children will experience a shift —described as ‘hitting a wall’ (Baldwin et al. 2019, p.218) — at around ages 11-12 years old when they move further in education, as they are no longer able to “fake” their abilities using compensating techniques (Baldwin et al. 2019).

Starling indicated that their favourite subject was maths (although what they are best at) and they need the most help with literacy. No assistance was noted on the card. Starling’s parent took the photograph and submitted it on Starling’s behalf.

Participant 3: Crow

Crow (not their real name) was a 10-year-old formally identified as gifted with a specific learning disability (SLD).

Crow’s parent/adult asked for extra time to complete but after follow-ups did not complete the task or offer explanation or additional information.

Conclusion and Recommendations

General & practical limitations

While probe kits have several positives, there are some limitations. Compared to a workshop where the researcher can supervise participants, a probe kit removes the ability to view the creative process. In this project, the limitations of a probe kit were weighed against the benefits of including participants from across the country and allowing neurodiverse children the space and comfort to have an enjoyable experience as participatory researchers.

Probe kits are particularly difficult to ensure the results are returned to the researcher. In this project six people initially expressed interest in participating (or having their child participate). Of the first six respondents, three participants shared their postal address to have a kit sent out, and two partial responses were returned.

The nature of this qualitative research and the small sample side mean the results can not be generalised across all contexts. The intentions are to provide an in-depth understanding of these 2e/DME’s children’s lived experiences and perspectives and empower them to participate in self-reflection and expression.

Conducting this research by workshop may have resulted in higher completion rates compared to using probe kits by mail. Probe kits were selected to remove the issue of travel and location and in theory open the pool of potential participants. Unfortunately, it proved difficult to obtain postal addresses and then to receive the kit responses back.

Probe kits also limit the amount of interaction with participants. In this project I was unable to watch the designs being completed and ask probative questions. Additionally, conducting this study as a workshop may also provide insights into peer support and the participants may have been better able to complete the designs with outside support.

Lived experiences of 2e/DME children

This research supports the idea that the lived experiences of 2e/DME children are unique. They show traits of both gifted and their other ‘exceptionality’ identities. It is evident they enjoy sharing about themselves and have interests both inside and out of school. Beyond all else, like Ronskley says, they are first and foremost children (Ronksley-Pavia 2015), with their own personalities, interests, and experiences. The best way to better understand them, and in turn help, is to continue to ask about their lives and experiences, listen and learn from them.

Further research

Even though the 2e/DME community is small, further research is this area is still needed. It is not a well-recognised identity (Robertson et al., 2011) and children can often be overlooked, with their learning difficulties overshadowing their gifted traits or vice-versa (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2013). As Baldwin et al. (2019, p.218) states, “twice-exceptional students must have a comprehensive, individualized, flexible plan that addresses the whole child.” More understanding and awareness of 2e/DME children will help them develop their strengths and overcome their weaknesses.

Received Images

Click on the slider arrows to scroll through photographs received from participants.

References

Baldwin, L., Omdal, S.N. and Pereles, D. 2019. Beyond Stereotypes: Understanding, Recognizing, and Working With Twice-Exceptional Learners. Teaching Exceptional Children . doi: 10.1177/0040059915569361.

Baum, S.M., Schader, R.M. and Hébert, T.P. 2014. Through a Different Lens: Reflecting on a Strengths-Based, Talent-Focused Approach for Twice-Exceptional Learners. Gifted Child Quarterly 58(4). doi: 10.1177/0016986214547632.

Beckmann, E. and Minnaert, A. 2018. Non-cognitive characteristics of gifted students with learning disabilities: An in-depth systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 9(APR). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00504.

Blesch, A. 2012. Sternberg’s Triarchic Theory of Intelligence. [Online]

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342918703_Sternberg’s_Triarchic_Theory_of_Intelligence

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Bornstein, M.H. and Gardner, H. 1986. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Journal of Aesthetic Education 20(2). doi: 10.2307/3332707.

British Mensa Ltd 2022. Mensa: Contact Us. [Online]

Available at: https://www.mensa.org.uk/contact-us

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Brody, L.E. and Mills, C.J. 1997. Gifted Children with Learning Disabilities: A Review of the Issues. Journal of Learning Disabilities 30(3), pp. 282–296. doi: 10.1177/002221949703000304.

Burge, A., Godinho, M.G., Knottenbelt, M. and Loads, D. 2016. ‘ … But we are academics!’ a reflection on using arts-based research activities with university colleagues. Teaching in Higher Education 21(6), pp. 730–737. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1184139.

Business Research Methodology [no date]. Positivism Research Philosophy. [Online]

Available at: https://research-methodology.net/research-philosophy/positivism/

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Comeau, E.T. 2016. Autism: 5 Things You Should Know About Children With ASD.

Creswell, J.W. 2018. Qualitative inquiry & research design : choosing among five approaches. Fourth edition / … Poth, C. N. ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Davidson Institute 2022. The Davidson Institute for Talent Development: What We Do. [Online]

Available at: https://www.davidsongifted.org/about-us/what-we-do/

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Eiserman, J., Lai, H. and Rushton, C. 2017. Drawing out understanding: Arts-based learning and gifted children. Gifted Education International 33(3). doi: 10.1177/0261429415576992.

Foley-Nicpon, M., Assouline, S.G. and Colangelo, N. 2013. Twice-Exceptional Learners: Who Needs to Know What? Gifted Child Quarterly 57(3), pp. 169–180. doi: 10.1177/0016986213490021.

Gagné, F. 2008. Building gifts into talents : Brief overview of the DMGT 2.0.

gov.uk 2021. Academic Year 2020/21: Schools, pupils and their characteristics. [Online]

Available at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

[Accessed: 24 May 2022].

Guignard, J.-H., Jacquet, A.-Y. and Lubart, T.I. 2012. Perfectionism and Anxiety: A Paradox in Intellectual Giftedness? PloS one 7(7), pp. e41043–e41043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041043.

Haines, M.E. 2017. Opening the doors of possibility for gifted/high-ability children with learning difficulties: preliminary assessment strategies for primary school teachers. Doctor of Education, University of New England.

Hawker, L. 2021. Dual and multiple exceptionalities: what you must know. tes magazine 6 December. [Online]

Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/teaching-learning/general/dual-and-multiple-exceptionalities-what-you-must-know

[Accessed: 24 May 2022].

Kassan, A. et al. 2020. Becoming new together: making meaning with newcomers through an arts-based ethnographic research design. Qualitative Research in Psychology 17(2). doi: 10.1080/14780887.2018.1442769.

Kellett, M., Forrest (aged ten), R., Dent (aged ten), N. and Ward (aged ten), S. 2004. “Just teach us the skills please, we’ll do the rest”: empowering ten-year-olds as active researchers. Children & society 18(5), pp. 329–343. doi: 10.1002/chi.807.

Kendall, L. and Allcock, C. 2020. A Brilliant IQ: Gift or Challenge? Brilliant Publications.

Lucinda 2016. Why Being British Stopped Me Finding Help For My Twice-Exceptional Child. [Online]

Available at: http://www.laughlovelearn.co.uk/2016/04/18/british-twice-exceptional-child

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Made By Dyslexia and Y&R London 2018. Dyslexic Sperm Bank. [Online]

Available at: https://www.dandad.org/awards/professional/2018/experiential/26537/dyslexic-sperm-bank/#:~:text=Dyslexic%20Sperm%20Bank%20%7C%20Y%26R%20London,Out%2Dof%2DHome%20%7C%20D%26AD

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Mcpherson, M. 2015. Labelling in Special Education. (Advantages and Disadvantages). [Online]

Available at: https://medium.com/@22Committed/labelling-in-special-education-advantages-and-disadvantages-55f7c6201170

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Murawski, W.W. and Scott, K.L. 2017. What Really Works with Exceptional Learners.

mygov.scot 2021. The PVG scheme. [Online]

Available at: https://www.mygov.scot/pvg-scheme#:~:text=The%20Protecting%20Vulnerable%20Groups%20(PVG,work’%20with%20these%20vulnerable%20groups.

[Accessed: 21 May 2022].

National Association for Gifted Children [no date]. About NAGC. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nagc.org/about-nagc

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Noel, L.-A. 2016. Promoting an emancipatory research paradigm in Design Education and Practice. In: Future Focused Thinking – DRS International Conference. [Online]

Available at: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1408&context=drs-conference-papers

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Olde Dubbelink, L.M.E. and Geurts, H.M. 2017. Planning Skills in Autism Spectrum Disorder Across the Lifespan: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47(4), pp. 1148–1165. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-3013-0.

Potential Plus UK 2020. Dual or Multiple Exceptionality. [Online]

Available at: https://www.potentialplusuk.org/index.php/families/dual-or-multiple-exceptionality/

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Robertson, S.G., Pfeiffer, S.I. and Taylor, N. 2011. Serving the gifted: A national survey of school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools 48(8), pp. 786–799. doi: 10.1002/pits.20590.

Ronksley-Pavia, M. 2015. A model of twice-exceptionality: Explaining and defining the apparent paradoxical combination of disability and giftedness in childhood. Journal for the Education of the Gifted 38(3), pp. 318–340. doi: 10.1177/0162353215592499.

Ronksley-Pavia, M., Grootenboer, P. and Pendergast, D. 2019a. Bullying and the Unique Experiences of Twice Exceptional Learners: Student Perspective Narratives. Gifted Child Today 42(1). doi: 10.1177/1076217518804856.

Ronksley-Pavia, M., Grootenboer, P. and Pendergast, D. 2019b. Privileging the Voices of Twice-Exceptional Children: An Exploration of Lived Experiences and Stigma Narratives*. Journal for the Education of the Gifted 42(1). doi: 10.1177/0162353218816384.

Sanders, E.B.-N. and Stappers, P.J. 2014. Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign 10(1), pp. 5–14. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2014.888183.

Stornelli, D., Flett, G.L. and Hewitt, P.L. 2009. Perfectionism, Achievement, and Affect in Children: A Comparison of Students From Gifted, Arts, and Regular Programs. Canadian journal of school psychology 24(4), pp. 267–283. doi: 10.1177/0829573509342392.

The Good Schools Guide [no date]. Dual or multiple exceptionality (DME). [Online]

Available at: https://www.goodschoolsguide.co.uk/special-educational-needs/types-of-sen/dme

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

University of Glasgow [no date]. Scottish Network for Able Pupils: About Us. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/ablepupils/aboutsnap/

[Accessed: 11 April 2022].

Yewchuk, C.R. and Bibby, M.A. 1989. The Handicapped Gifted Child: Problems of Identification and Programming. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l’éducation 14(1), pp. 102–108. doi: 10.2307/1495205.