The Modern Makerspace

This research project explores the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on makerspaces in the urban environment. With particular interest in how makers, and makerspaces have kept in touch with each other and the larger community during the pandemic as well as any changes to this relationship post-pandemic.

About

Brief: We were tasked with gathering diverse forms of data that tell us something about Post-Covid Touch in the City.

Opportunity: I started this project by using walking as method, I took videos of touch-less interactions, photos of touch points in the city, but it didn’t express what I was really interested in. I started thinking about touch as emotional, social – I wanted to know how have we kept in touch with each other, and more specifically with the city’s makerspaces. Generally a space to gather, and make things – which usually involves touching a lot of materials.

Objective: Investigate the impact and effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on makerspaces in the city and their touch with the community.

Stakeholders: Makers, Researchers, Designers, Policy Makers, Artists, Creatives

The Modern Makerspace: Keeping touch with making and craft in the post-covid city

Introduction & Aim

On the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organisation declared the Covid-19 outbreak a global pandemic (cited in Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020) and since then the UK and the globe have been waiting for ‘post-Covid’ to begin. As of October 2021, Scotland, and much of the UK are still experiencing some form of government restrictions.

The Covid-19 restrictions changed a lot about how we live in urban environments, how we keep in touch with each other, and what we can physically touch. Many aspects of live and the city have been affected, including makers and makerspaces.

This project investigates not just how our physical touch within these spaces changed, but also the emotional effects of the pandemic. Questions this research aims to investigate include: How have makerspaces physical space changed? How can makers stay in touch with their communities? And what is the future for makerspaces in the city?

Aim: The aim of this research was to investigate the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on makerspaces in the city and their state post-pandemic.

Methods and Processes: What I Did, Why, and How

Mapping

This project started with mapping as a method of research, looking for the locations of makerspaces in the city.

A Study of Lived Experiences using Multi-Modal Phenomenological Research

Phenomenology is an approach to research that concentrates on lived experiences (Creswell 2018). There are many methods that can be used in phenomenological research including, interviews, conversations, participant observation and action research (Lester 1999). It is in this spirit of learning from lived experiences that I developed my multi-modal research approach.

Personal Interviews

My research included using semi-structured interviews of owners or members of urban makerspaces, on site. This allowed me to combine conversational style interviewing with photography and observation of the space to better understand in person what they were like. Interviews are important in qualitative research as they allow for a deep understanding and possibility of asking follow-up questions (Hannabuss 1996).

Research Through Making & Observative Research

If phenomenology can be described as a “way of thinking about knowledge – a philosophical and theoretical viewpoint – how do we know what we know” (cited in Qutoshi 2018, p.5), and if craftspeople tell stories through their craft (Ingold 2020) – then why not also participate in making in the makerspaces?

I could use a variety of terms to describe this method of research, it could be considered a type of craft research or action research. I might even be able to argue it is like anthropological field research. For this project I am describing my method as ‘research through making.’ Along with interviewing makers, I joined either a class or a workshop hosted in their space to gain a richer understanding of the lived experience, and the made objects became part of the research material as well. This additional method allowed me a better understanding than using just interview or photography of the space alone.

I could use a variety of terms to describe this method of research, it could be considered a type of craft research or action research. I might even be able to argue it’s similar to an anthropological type of field research. For this project I am describing my method as ‘Research through making’. Along with interviewing makers, I joined either a class or a workshop hosted in their space to gain a richer understanding of the lived experience, and the made objects became part of the research material as well. This additional method allowed me a better understanding than using just interview or photography of the space alone.

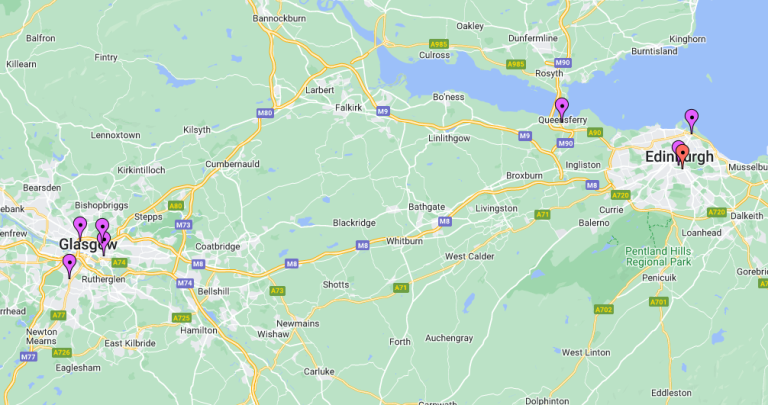

Mapping Makerspaces

I started by mapping out makerspaces I could find searching online. I looked only for urban makerspaces, and excluded any rural ones, or those outside the city. I marked in red the one which was closed but still planning to open again.

The map is available online at: https://www.zeemaps.com/map?group=4411840

Vanilla Ink

Vanilla Ink is a Glasgow based jewellery and craft workshop and makerspace that was founded in 2017 after receiving £30,000 in crowdfunding. They host a variety of classes and workshops that less experienced makers can join, as well as providing rental bench space for more trained jewellers to work on their craft. They also offer a bespoke jewellery commissions service “using a cross between traditional techniques and modern methods” (Vanilla Ink 2021).

Vanilla Ink is a Community Interest Company and describes the aim of their social enterprise work on their website as follows:

“Our aim is to use making as a form of therapy for escapism and to create a real sense of achievement. We strive to work with the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in society for the greater good, using our skills to enhance people’s lives.” (Vanilla Ink 2021)

Scott McIntyre is the creative director with over 26 years of experience working with a variety of jewellers before developing his own school program. (Vanilla Ink, 2021). I had the pleasure of meeting Scott during the depths of the Covid 19 Pandemic in September/October 2020 when I joined the Vanilla Ink’s ‘Make your own wedding rings’ workshop. I took the opportunity this project presented to reach out to Scott for an interview, and to see how things may have changed since then.

Vanilla Ink

I met with the founder Scott (19 October 2021), and we had a very semi-structured interview, which was more of a directed conversation about how the Vanilla Ink Makerspace was affected by the pandemic, what they were doing now and going forward.

View full transcript here.

I also signed up for a sea-glass ring making workshop on the 2nd of April 2022 to experience the makerspace post-covid first hand. I was lucky to grab the last available space on this class – many of the earlier and other types of classes were fully booked.

Glasgow Glass Studio

The Glasgow Glass studio had an open studio event in October 2021 where they were offering some making taster activities.

Unfortunately, when I arrived, I learnt that the main organiser had been exposed to Covid, so was not able to come down. Some materials had been left for the making experience, and I was able to create a glass tree while I was there.

Glasgow Glass Studio

I had an enjoyable conversation with a local glass artist, who showed me around the studio and some of his work. He said that his work was not affected much by the pandemic, he was still getting private requests, and he likes to work in isolation anyway. He did say that the classes offered in the studio suffered due to the restrictions.

The following photos are of my experience at the Glasgow Glass Studio:

Edinburgh Remakery

I joined a making class at the Edinburgh Remakery on the 16th of April 2022 to get the experience of a makerspace once we had entered what really started to feel like “Post-Pandemic”.

The instructor was incredibly happy to have a full class in attendance (although it was still small), and we were not required to wear masks. The rest of the studio was noticeably quiet, but it appears that they like to schedule classes at slower times. The instructor was not able to provide many insights into the makerspace during the pandemic as she just comes in to teach the class – just that her class had been cancelled for a while.

The Remakery

Who else has done something similar (in design practice and research)

Map of creative industries in south-east Scotland

Bruce Ryan from Napier’s Creative Infographics has created a map with data about creative industries in south-east Scotland. The map shows creative companies according to their Department for Culture, Media and Sports codes, and their Scottish Creative and Cultural Industries codes (Ryan 2021).

Covid-19 response from global makers

Kieslinger et al. conducted a study on makerspaces during the pandemic, they concentrated on the makerspaces that changed to start producing objects to support the covid efforts – such as door openers, and ear savers to intubation boxes (Kieslinger et al. 2021). Their research primarily uses case study as method concentrating and researching in detail on only a few makerspaces.

Corsini et al. also conducted research on makers during the pandemic, specifically looking at “the digital fabrication responses of the maker community to COVID-19 through the lens of frugal innovation” (Corsini et al. 2021, p.196). This is a smaller study, concentrating on a few examples to support discussion of frugal innovation. Calvo et al.’s study is similar but in the context of Spanish makers (Calvo et al. 2021)

Impact of Covid-19 on creative sectors

Travkina and Sacco on behalf of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a report on the impact of the pandemic on cultural and creative industries. They reported that “Along with the tourism sector, cultural and creative sectors (CCS) are among the most affected by the current crisis, with jobs at risk ranging from 0.8 to 5.5%of employment across OECD regions” (Travkina and Sacco 2020, p.2). This was despite the rapid innovation of the industry, as noted by Corsini et al., and Corsini et al.

Findings & Reflection

The most insightful interview I had was with Scott at Vanilla Ink in Glasgow. They were (like many others) impacted by the pandemic, both personally and to the business. Their business is also a social enterprise, and they did try to keep the sense of community going during lockdown using a variety of digital tools, such as Facebook live and Instagram. They froze rents to their makers while still paying their landlord for the space, and even though they applied for government funding, it was not enough to cover the expenses. They were in dire need of re-opening to keep going. Scott also said it started to feel quite empty in the space on his own, or so far apart from other people when they did resume small amounts of activities at distance. He did say that it was quite difficult to show people things as you were not allowed to touch certain objects or be close to each other.

Vanilla Ink is for both professionals and hobbyists. Since the lockdowns, Scott has noticed an increase of interest in his classes, and their classes booked up quickly once things started opening again. He commented that most of the people he has joining in his taster sessions are professional women working in the NHS. They come as a way of relieving stress, they are also particularly good with their hands (some are surgeons or physiotherapists).

“The lockdown has made evident the importance of culture for people’s well-being and mental health. What is more, the emerging link between arts and culture production and participation with health and well-being could provide opportunities for prevention of illness and treatment of diseases for health systems.” (Travkina and Sacco 2020, p.3).

When I attended my ‘taster session’ class (sea-glass ring making) I noticed that every attendee was female. Several of them also said they had received the class as a gift.

I enjoyed the taster session, it was great to get out of the house, and I even used the excuse to go to the beach for some sea glass hunting the weekend before (they had some available, but you could bring your own). The instructors worked extremely hard with the various skill levels in the class to ensure we all walked away with something. We did not wear any masks, but it we discussed masks at the beginning of class, it was clear that we could if we wanted and could ask if we wanted others to. Everyone was ok with pretending Covid did not exist and we were in our own world.

At the Glasgow Glass Studio and the Edinburgh Remakery, I get to experience what the spaces were like, but my opportunity to interview knowledgeable people was limited. However, the feeling seemed universal, that they were also affected by the pandemic, had attempted to make online options but were really looking forward to, or happy to be back open.

My mapping exercise was limited, and could have used more data input, but it was helpful in seeing what was easily accessible at the time.

Overall, this project shows some real insights into the effects of the pandemic on makerspaces keeping in touch with their communities. Hopefully, it also shows the importance of these spaces in our social and cultural lives.

References

Calvo, D., Yauri-Miranda, J.R. and Haro-Barba, C. 2021. Design, Manufacture and Save. Coronavirus Makers During the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. Javnost – The Public 28(3), pp. 273–289. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2021.1969618.

Corsini, L., Dammicco, V. and Moultrie, J. 2021. Frugal innovation in a crisis: the digital fabrication maker response to COVID‐19. R&D Management 51(2), pp. 195–210. doi: 10.1111/radm.12446.

Creswell, J.W. 2018. Qualitative inquiry & research design : choosing among five approaches. Fourth edition / … Poth, C. N. ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Cucinotta, D. and Vanelli, M. 2020. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomedica 91(1), pp. 157–160. [Online]

Available at: https://www.mattioli1885journals.com/index.php/actabiomedica/article/view/9397

[Accessed: 1 October 2021].

Hannabuss, S. 1996. Research interviews. New Library World 97(5), pp. 22–30. doi: 10.1108/03074809610122881.

Ingold, T. 2020. Of Work and Words: Craft as a Way of Telling Stories. European Journal of Creative Practices in Cities and Landscapes 2(2 SE-)

Kieslinger, B. et al. 2021. Covid-19 Response From Global Makers: The Careables Cases of Global Design and Local Production. Frontiers in Sociology 6. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.629587.

Lester, S. 1999. An introduction to phenomenological research. Stan Lester Developments. [Online]

Available at: http://www.sld.demon.co.uk/resmethy.pdf

[Accessed: 1 October 2021].

Qutoshi, S.B. 2018. Phenomenology: A Philosophy and Method of Inquiry. Journal of Education and Educational Development 5(1). doi: 10.22555/joeed.v5i1.2154.

Ryan, B. 2021. Mapping creative industries in south-east Scotland. Social Informatics Research Blog at Napier University. [Online]

Available at: https://blogs.napier.ac.uk/social-informatics/2021/12/mapping-creative-industries-in-south-east-scotland/

[Accessed: 1 March 2022].

Travkina, E. and Sacco, P.L. 2020. Culture Shock: COVID-19 and the Cultural and Creative Sectors. OECD

Vanilla Ink 2021. Vanilla Ink. [Online]

Available at: https://vanillainkstudios.co.uk/

[Accessed: 1 October 2021].